Treaties Recognition Week was introduced in 2016 to honour the importance of treaties and to inform about treaty rights and treaty relationships. Reconciliation is about healing and it begins with a commitment to learn about, respect, and honour First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. Treaties Recognition Week is one element the reconciliation path.

Treaties are constitutionally recognized agreements between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown. Indigenous peoples did not intend to surrender their land, but rather thought of treaties in terms of promises, sharing, and mutual support. Settlers and colonial administrators often betrayed these agreements. Treaties Recognition Week offers us all a chance to reflect and learn.

Understanding treaties can be complex. To learn more about treaties and treaty relationships, please visit:

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/aboriginal-treaties

http://mncfn.ca/about-mncfn/treaty-lands-and-territory/

https://archive.org/details/indiantreaties0102cana/page/n125/mode/2up

The City of Mississauga is connected to five treaties signed between The Crown and the Indigenous Mississaugas between 1805 and 1820: Provisional Agreement 13-A, Treaty 14, Treaty 19, Treaty 22 and Treaty 23.

By the 1790s, the British Crown recognized that the Indigenous Mississaugas controlled a large amount of land at the western end of Lake Ontario, which had come to be referred to on early maps as the “Mississauga Tract”. The Crown entered into a series of negotiations and treaties to acquire this tract for settlement. At the end of July of 1805 representatives of the British Crown convened a meeting with the principal chiefs of the Mississauga near the mouth of Credit River. These negotiations were held outside and in close proximity to the Government Inn.

By the 1790s, the British Crown recognized that the Indigenous Mississaugas controlled a large amount of land at the western end of Lake Ontario, which had come to be referred to on early maps as the “Mississauga Tract”. The Crown entered into a series of negotiations and treaties to acquire this tract for settlement. At the end of July of 1805 representatives of the British Crown convened a meeting with the principal chiefs of the Mississauga near the mouth of Credit River. These negotiations were held outside and in close proximity to the Government Inn.

The Crown was represented by Colonel William Claus, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, with other officials and officers from the 49th Regiment. The Mississaugas were represented by their principal chiefs and a gathering of warriors. The Chiefs of the Mississaugas understood that the Crown wished to share their land, although they were wary of relinquishing too much of their territory. The Mississaugas hoped that a treaty would protect their traditional hunting and fishing rights, and reduce potential conflicts over land and resources in regards to incoming settlers.

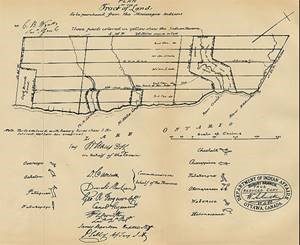

During the negotiations Chief Quenippenon (Quinipeno, Kineubenae, Quenepenon), and also known as “Golden Eagle”, produced a map etched on a flat stone that outlined the Mississauga territory under negotiation. Speaking on behalf of the Mississaugas, Quenippenon stated their concerns:

… we were told our Father the King wanted some Land for his people it was some time before we sold it, but when we found it was wanted by the King to settle his people on it, whom we were told would be of great use to us, we granted it accordingly. Father – we have not found this so, as the inhabitants drive us away instead of helping us, and we want to know why we are served in that manner … Colonel Butler told us the Farmers would help us, but instead of doing so when we encamp on the shore they drive us off and shoot our Dogs and never give us any assistance as was promised to our old Chiefs … Now Father you want another piece of land – we cannot say no, but will explain ourselves before we say any more … I speak for all the Chiefs & they wish to be under your protection as formerly, But it is hard for us to give away more Land: The young men and women have found fault with so much having been sold before; it is true we are poor, & the women say we will be worse, if we part we part with any more …

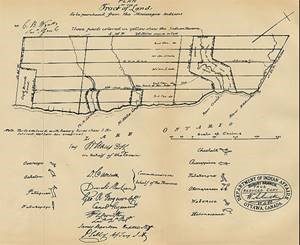

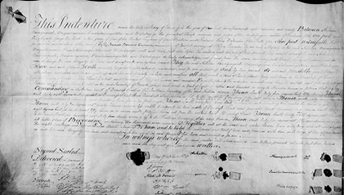

Eventually the Mississaugas agreed to the Crown’s request for territory. The Crown and the Mississaugas signed two treaties during this negotiation. On August 1, 1805, Treaty 13 was agreed upon, which clarified an earlier treaty from 1787 and involved land east of the Etobicoke Creek. The following day, on August 2, 1805, Provisional Agreement 13-A was signed. Referred to as the “First Purchase” or the “Mississauga Purchase”, this agreement involved 70,784 acres of land, involving all lands from the Etobicoke Creek to Burlington Bay to an approximate depth of 6 miles from the shoreline. The southern part of the City of Mississauga, from Lake Ontario to Eglinton Avenue, is located within this area. This agreement was ratified with the signing of Treaty 14 on September 5, 1806, also known as the “Head of the Lake Purchase”. The Mississauga’s were compensated 1000 pounds of Province currency, given largely in trade goods over several years.

Provisional Agreement 13-A was signed by William Claus, Esq., Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Crown, together with Mississauga Chiefs Chechalk, Quenippenon, Wabukanyne and Okemapenesse. The signing was witnessed by J.W. Williams, Captain 49th Regiment, John Brackenbury, Ensign 49th Regiment, Peter Selby, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and Scribe, and translator J.B. Rousseaux.

Provisional Agreement 13-A was signed by William Claus, Esq., Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Crown, together with Mississauga Chiefs Chechalk, Quenippenon, Wabukanyne and Okemapenesse. The signing was witnessed by J.W. Williams, Captain 49th Regiment, John Brackenbury, Ensign 49th Regiment, Peter Selby, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and Scribe, and translator J.B. Rousseaux.

In this agreement, the Mississaugas reserved rights to the fisheries in the Twelve Mile Creek, Sixteen Mile Creek and the Etobicoke Creek, and sole right to the fishery in the River Credit along with one mile each side of the river. This area became known as the Credit Indian Reserve:

We, the Principal Chiefs of the Mississague Nation, for ourselves and on behalf of our Nation, do hereby consent and agree with William Claus, Esquire, Deputy Superintendent General and Deputy Inspector General of Indian Affairs, on behalf of His Majesty King George the Third, that for the consideration of one thousand pounds Province currency, in goods at the Montreal price, to be delivered to us, we will execute a regular deed for the conveyance of the lands … containing seventy thousand seven hundred and eighty-four acres, whenever the goods of the aforesaid value shall be delivered to us. Reserving to ourselves and the Mississague Nation the sole right of the fisheries in the Twelve Mile Creek the Sixteen Mile Creek, the Etobicoke River, together with the flats or low grounds on said creeks and river, which we have therefore cultivated and where we have our camps. And also, the sole right of the fishery in the River Credit with one mile on each side of said river.

The “Head of the Lake Purchase”, or Treaty 14, was signed William Claus on behalf of The Crown, and Mississauga Chiefs Chechalk, Quenepenon, Wabukanyne, Okemapenesse, Wabenose, Kebonecence, Osenego, Acheton, Pataquan and Wabakagego. The signing was witnessed by D. Cameron, Donald MacLean, George Ferguson, Captain of the Canadian Regiment, William Crowther, Lieutenant 41st Regiment, James Davidson, Hospital Staff, H.M. Smith, Peter Selby, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, J.B. Rousseaux and David Price, Interpreter. Treaty 14 reaffirmed the importance of the fisheries at Twelve Mile Creek, Sixteen Mile Creek, Etobicoke Creek and the Credit River to the Mississaugas’ way of life.

On October 28, 1818 the Crown and the Mississaugas, signed Treaty 19, also known as the “Ajetance Treaty”, which involved 648,000 acres of land (all lands north of modern Eglinton Avenue). Treaty 19 was signed by William Claus, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Crown and Mississauga Chiefs Adjutant (Ajetance), Weggishgomin, Cabibonike, Pagitaniquatoibe and Kawahkitahaquibe. The agreement was witnessed by James Givins, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Hands Jr., Clerk of the Indian Department, and William Gruet, Interpreter for the Indian Department.

The completion Treaty 19 left the Mississaugas with three small reserves at 12 Mile Creek, 16 Mile Creek, and the Credit River. Noting the distress and poverty of the Mississaugas, William Claus, Deputy Superintendent of the Indian Department, met with the Mississaugas and proposed the surrender of their remaining lands.

Claus promised that the proceeds of the sale would be used to instruct the Mississaugas in the rudiments of the Christian religion and to provide education for their children. In addition, a portion of land consisting of 200 acres located in southeasterly portion of the Credit River Reserve would be set aside as a village site for the Mississaugas.

On February 28, 1820 Treaties 22 and 23, referred to as the “Credit Treaties”, were signed and the Crown acquired the reserve lands, which had been set aside in the 1805 agreement.

According to the terms of Treaty 22, the Mississaugas acquiesced to the Crown’s demand for lands at 12 and 16 Mile Creeks along with northern and southern portions of the Credit River Reserve. Treaty 23, negotiated later the same day, involved the central portion of the Credit River Reserve, along with its woods and waters.

and 16 Mile Creeks along with northern and southern portions of the Credit River Reserve. Treaty 23, negotiated later the same day, involved the central portion of the Credit River Reserve, along with its woods and waters.

Treaties 22 and 23 were signed, once again, by William Claus, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of The Crown, along with Mississauga Chiefs Acheton (Adjutant, Ajetance, “Captain Jim”), Woiqueshequome (Weggishgomin, Okemapenesse, “John Cameron”), Novoiquequah, Paushetaunonquitohe and Wabakagego. The agreements was witnessed by James Givins, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Alexander McDonell, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, William Gruet, Interpreter for the Indian Department, D. Cameron, N. Coffin, and members of the 68th Regiment.

The Credit Indian Reserve lands along the Credit River were retained by The Crown as the Credit Indian Reserve until March of 1846 when the lands were surveyed and put up for auction.

All five of the agreements and treaties involving what is now the City of Mississauga had two constants: all were signed by William Claus on behalf of The Crown and Mississauga Chief Okemapenesse/Weggishgomin/”John Cameron” on behalf of the Indigenous Mississaugas.

Understanding treaties and concepts of land use is complex and is a key component of reconciliation. Governments often interpreted treaties as legal documents that ceded or surrendered land – a type of real estate purchase of Indigenous lands – and as such a surrender of Indigenous rights and claims to land.

For Indigenous peoples, treaties were sacred covenants of trust, and that the true character of the agreements is not found in the legal descriptions, but in what was said during negotiations. Treaties were often accompanied by traditional ceremonies, such as the smoking of pipes or an exchange of wampum belts. The Indigenous view, treaties are seen as instruments of sacred relationships between autonomous peoples who agreed to share lands and resources. Seen from the Indigenous perspective, treaties do not surrender rights; rather, they confirmed Indigenous rights.

Indigenous peoples regarded the promises outlined in the treaties as sacred and enduring; however history has shown that Crown representatives did not. Negotiations were often conducted in bad faith. In regards to the Mississaugas, they entered into treaties with The Crown seeking mutual respect and co-operation, although as shown by Chief Quenepenon’s remarks in 1805, the Mississaugas were already wary of broken promises. Over the many years since these treaties were signed, the relationship between The Crown and the Indigenous Mississaugas have been eroded by colonial policies that were enacted into laws. Understanding treaties rights and seeking to resolve specific claims is a beginning towards understanding and honouring treaty obligations.

Please join us for our Historic Walking Tour on November 12, 2022 at 11:00 a.m. as we explore the connection of these treaties to Port Credit.

Register here.

Written by Matthew Wilkinson,

Historian, Heritage Mississauga

PCBIA acknowledges the lands which constitute the present-day Port Credit as being part of the Treaty and Traditional Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, The Haudenosaunee Confederacy the Huron-Wendat, and Wyandot Nations. We recognize these peoples and their ancestors as peoples who inhabited these lands since time immemorial.

The Port Credit BIA is actively working to acknowledge and celebrate the Indigenous history of these lands, to collaborate with Indigenous peoples to instill a sense of connection and belonging in Port Credit, and to create a safe space for Indigenous peoples within their territory.

By the 1790s, the British Crown recognized that the Indigenous Mississaugas controlled a large amount of land at the western end of Lake Ontario, which had come to be referred to on early maps as the “Mississauga Tract”. The Crown entered into a series of negotiations and treaties to acquire this tract for settlement. At the end of July of 1805 representatives of the British Crown convened a meeting with the principal chiefs of the Mississauga near the mouth of Credit River. These negotiations were held outside and in close proximity to the Government Inn.

By the 1790s, the British Crown recognized that the Indigenous Mississaugas controlled a large amount of land at the western end of Lake Ontario, which had come to be referred to on early maps as the “Mississauga Tract”. The Crown entered into a series of negotiations and treaties to acquire this tract for settlement. At the end of July of 1805 representatives of the British Crown convened a meeting with the principal chiefs of the Mississauga near the mouth of Credit River. These negotiations were held outside and in close proximity to the Government Inn. Provisional Agreement 13-A was signed by William Claus, Esq., Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Crown, together with Mississauga Chiefs Chechalk, Quenippenon, Wabukanyne and Okemapenesse. The signing was witnessed by J.W. Williams, Captain 49th Regiment, John Brackenbury, Ensign 49th Regiment, Peter Selby, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and Scribe, and translator J.B. Rousseaux.

Provisional Agreement 13-A was signed by William Claus, Esq., Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Crown, together with Mississauga Chiefs Chechalk, Quenippenon, Wabukanyne and Okemapenesse. The signing was witnessed by J.W. Williams, Captain 49th Regiment, John Brackenbury, Ensign 49th Regiment, Peter Selby, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and Scribe, and translator J.B. Rousseaux. and 16 Mile Creeks along with northern and southern portions of the Credit River Reserve. Treaty 23, negotiated later the same day, involved the central portion of the Credit River Reserve, along with its woods and waters.

and 16 Mile Creeks along with northern and southern portions of the Credit River Reserve. Treaty 23, negotiated later the same day, involved the central portion of the Credit River Reserve, along with its woods and waters.